The Appalachian Chronicle

I – LAKE CITY, Tenn. – On Oct. 26, a reception to celebrate the life of Charles “Boomer” Winfrey was held for his family, friends, colleagues and admirers. The gathering was held at the Coal Creek Miners Museum that he founded.

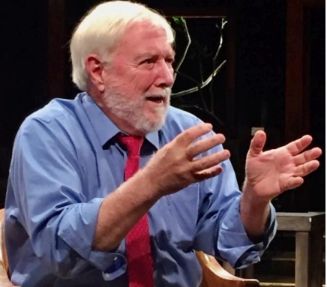

Charles “Boomer” Winfrey

Mr. Winfrey, 76, passed away on Oct. 6, 2023. His death is clearly a loss to those who loved him, met him and were lifelong learners interested in learning all he knew – which was unmatched – about the beginning of the Coal Wars.

Fortunately, he graciously agreed to an interview after going into Hospice care and just days before he passed. He was engaged as ever in a phone interview sharing what and why he has spent his life teaching about the extraordinary history of the community in which he was born.

He was expert at focusing on the important events and their significance of this season of miner unrest and mine disasters. Indeed, this town’s evolving names reflect it’s complex history. At the time of the these first coal wars, the community was known as Coal Creek. Years later, it became Lake City. More recently, it changed its name again, this time to Rocky Top.

THE CONVICT LEASE SYSTEM

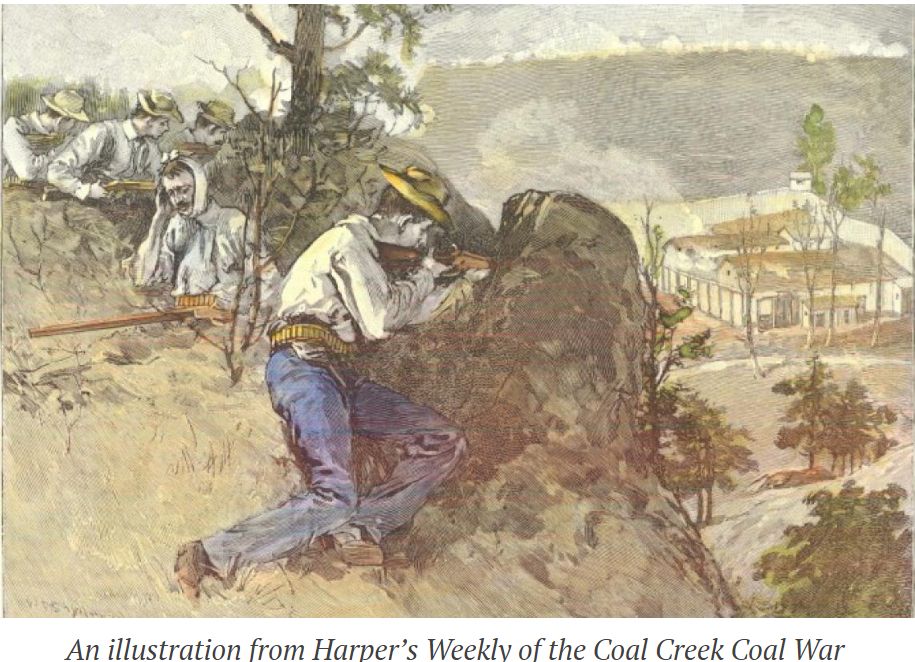

East Tennessee is not generally the place one thinks of as the starting point of the Coal Wars between miners and mine operators. Make no mistake about it though. It was, as miners engaged mine owners and then the Tennessee National Guard in numerous skirmishes and guerrilla actions following the Civil War, noted Mr. Winfrey.

“This was a shooting war!” exclaimed Mr. Winfrey. He continued, “But it wasn’t about forming a Union. There was none until 1891.” Though miners did strike and generally create havoc for their company and political overlords for a season, Mr. Winfrey made clear that the struggle was not about Union organizing, emphasizing, “It was about the Convict Lease System.”

The reason? Tennessee’s industrialists and politicians conspired to replace slavery with prison labor. Mr. Winfrey shared, “About every state in the old Confederacy put it in place. They found it as a convenient way to replace slavery. They started passing laws that would sentence someone to a year in prison, making them eligible to serve their sentence as mine laborers. They picked on blacks especially.” Indeed, soon after the program was initiated, the black prison population increased by more than 10,000 people, mostly all arrested, “tried” and imprisoned on trumped-up charges.

In 1877, the Knoxville Iron Works opened the first coal mine in Coal Creek. Well before 1891, the use of convicts to replace miners had begun. “Nobody paid attention until 1891,” noted Mr. Winfrey. “But at the Briceville Company town the prisoners were required to destroy the miners’ houses and build a stockade for themselves. That was too much for the miners. They loaded up the trains and told the governor not to send back any more convicts.”

He continued, “The governor sent them back and returned with them. After he left, the miners again overcame the guards, but this time freed the prisoners and told them, ‘Kentucky is that way fellas.”

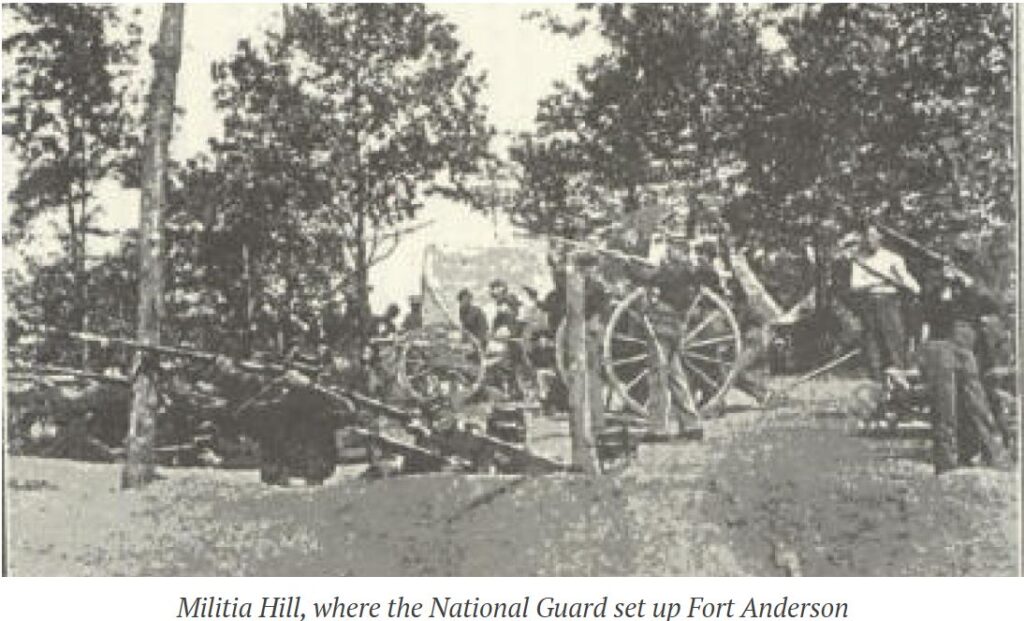

That was when the militia was sent in. A fort was built overlooking the town, though miners more familiar with their home territory went to higher ground, constantly harassing the militia. By 1892, though, the firepower of the state militia was too much and the ongoing battle finally ended. “They lost the battle, but they won the war,” offered Mr. Winfrey, explaining, “It was the end of convict lease system. Once this happened in Tennessee, the other states could see the writing on the wall.” The last state to abandon the system was Alabama in 1913.

Essentially, said Winfrey, “They realized that maintaining a standing army was too expensive.” Indeed, the state of Tennessee built the Brushy Mountain State Prison as a replacement to the Convict Lease System.

There are important lessons from the early days of coal mining labor strife in East Tennessee, observed Winfrey. Of the Convict Lease System he said, “This was the first time that people had rose up against this in armed opposition and it was done away with.” He noted that the tragic mine disasters led to the establishment of federal oversight of mine safety and led to improvement in safety practices.

© Michael M. Barrick, 2023, The Appalachian Chronicle

II – Note: This is the second in a series on the “When Miners March Traveling Museum/Our Story Exhibit” by Wess Harris. Read the first article here.

GAY, W.Va. – Twenty years ago, in what Wess Harris characterizes as “a complete accident,” he met William C. Blizzard, whose accounts of the West Virginia Mine Wars had been lost to time.

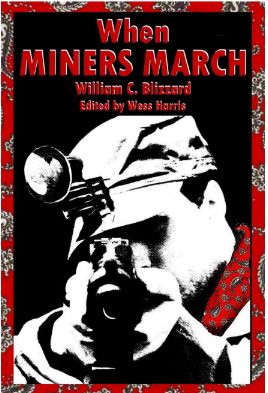

The unlikely story began when Harris, a sociologist, educator, farmer, former miner, author and editor was following his passion – labor history, in particular of the West Virginia Mine Wars. Harris is the founder and curator of the “When Miners March Traveling Museum.” Without that chance meeting between Harris and Blizzard, there would be no traveling museum, for it is based on the book, “When Miners March: The Story of Coal Miners in West Virginia,” written by Blizzard decades ago. Harris published the first edition along with Blizzard in 2004. A second edition was printed by PM Press in 2010. Blizzard passed away in 2008 at 92-years-old.

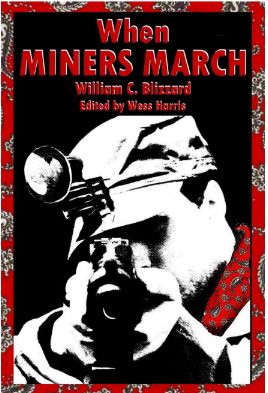

Bill Blizzard on the first edition cover

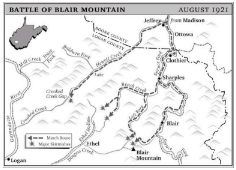

William C. Blizzard was the son of Bill Blizzard. As Harris notes in the Foreword, “Bill Blizzard was the chief protagonist in the drama played out around Blair Mountain. He led the miners’ Red Neck Army as they marched toward Logan County in 1921, hoping to bring the United Mine Workers to the scab mines of Logan and Mingo Counties.” As Harris explains, “The 1921 Battle

of Blair Mountain in which thousands of miners formed an army to unionize the southern West Virginia coal fields is a story oft told.” The younger Blizzard wrote numerous articles in the 1940s and early 1950s about the West Virginia Coal Wars. Harris explains in the Foreword, “This work was originally offered in serial form, titled, ‘Struggle and Lose…Struggle and Win!’ in the newspaper, ‘Labor’s Daily,’ of late ‘52 and early ‘53.’”

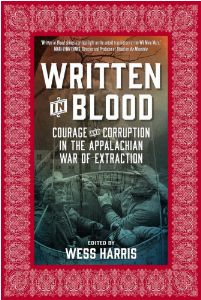

Second edition cover

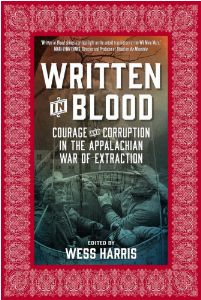

The articles were published without bylines. So, the younger Blizzard’s work contained thorough but largely ignored history until Harris met him. That history, as it turned out, is but the tip of the iceberg, as even more stories of industry abuse of miners and their families has been told in a second book edited by Harris and published by PM Press, “Written in Blood: Courage and Corruption in the Appalachian War of Extraction.”

Harris has traveled West Virginia and beyond, teaching labor history, with a focus on the United Mine Workers (UMW). While doing so, he has sold thousands of copies of “When Miners March.”

Indeed, if not for a question he asked Blizzard as an afterthought as he was leaving, Harris would have missed out on what has become his life’s work since he asked that question. Harris was on one of his explorations looking for people and places that could add to his knowledge of labor organizing, unions and their history, in particular the work of Connie West, a groundbreaking educator along with her husband Don, as well as a portrait painter of people essential to West Virginia’s coal history. Somebody told Harris about a fellow that might be able to help him.

It was William C. Blizzard

Harris recalls, “Basically, back in 2004 as a complete accident, I met William C. Blizzard. He was living in Winfield right along the Kanawha River in an old single wide. There were wires, computers and printers everywhere. I didn’t know who he was. People said he knew Connie West.”

They met and talked for a while, then as Harris prepared to leave, he offhandedly asked him, “Did you know that Blizzard in the Mine Wars? He looked at me, hand on his chin and said, ‘Well, that was my daddy.’”

Harris continues, “I found out he had this manuscript. Nobody knew it existed. William C. had published it in the Huntington Labor Daily. I learned he had all of these artifacts from his dad. I immediately knew, There goes the rest of my life.’ I immediately began trying to get him to print the thing. I knew it was an incredible history that hadn’t been told.”

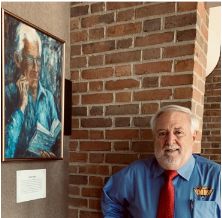

Wess Harris teaching. Photo by Nellie Blanton

As it turned out, Harris was familiar with some of the manuscript. He explains, “In the 1970s, I was teaching at the West Virginia Career College at Morgantown. All of the students were veterans from the Vietnam era. At some point, a student came up and handed me a copy of papers from the newspaper. I used it as the teaching base.” He adds, “I didn’t know it was William C. Blizzard’s work.”

He continues, “It was initially titled ‘Struggle and Lose…Struggle and Win.’ It’s a Mother Jones quote. I realized that what I had in my hands was an incredible treasure that nobody knew about that hadn’t been seen for 25 years, yet it is a vital history of the state.”

Harris was amazed. “I knew Bill was important in the Mine Wars, but I didn’t know how much. I tried to get a major publisher to take it, but they wanted to edit it. I said no way. It’s a primary source.” So, he published it as originally written. “We sold 5,000 copies.” He adds, “I was teaching at a book festival in Charleston and some guy from PM press saw me.” They reached an agreement to continue publishing the book. “After that, the book legacy kept rolling,” shares Harris. “As people found out about it, they started giving me artifacts. Knowing I was serious, I’ve had many rare and top quality artifacts given or loaned to me. People have been incredibly supportive. They know the history has not been told.”

He says that because his objective is to teach, he generally allows people to handle or at least touch artifacts, which is the opposite of what most museums would allow. “I always say yes,” offers Harris.

That’s true about artifacts, but also his overall commitment to ensuring William C. Blizzard’s accounts of the West Virginia Mine Wars are told. “It’s just incredible. It is the history that hasn’t been told.”

Heidi Perov courtesy of WV Humanities Council

Indeed, insists Harris, “I didn’t have a choice. It just had to be done. I could give you a book on what I have learned. I was a board member of the West Virginia Labor History Association. As time went on, they threw me off the board. What I learned is that nobody is really doing this work. To go out and look for it and teach it. Nobody does the work. So I decided to just get out there and do it.”

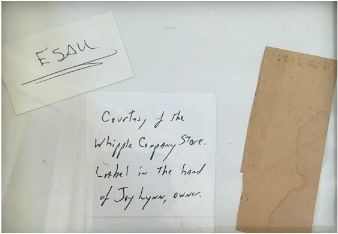

Yet, he is concerned. “We’re losing this history. Some of it, like Esau scrip, is just not being told, and in fact is being actively censored. Everyone is dead. Research methodology is just horrible. You’ve got to do your own homework. I tell

people don’t believe a word I say. Don’t believe anybody else either.”

The decades of study, research and chatting it up with those who share first-hand accounts has taught Harris much. “There’s a whole history about the labor movement in coal mining. What I’ve learned about coal is that it’s all about the money.” Yet, he argues, the UMW is not currently positioned to effectively champion worker rights. “A lot of my education and previous study of formal organizations teaches me that the UMW has matured and done what all organizations have done – gotten outflanked.”

He adds, “I don’t mean just our Union, I mean me. The miners and the mining communities. We had best look at new solutions. The old solutions don’t work. As the rules get tighter by the people who own the companies and politicians, we just can’t be stuck in a rut. We can learn from the past but create the new future. You have to understand the history to understand where we are so we don’t repeat that. We’re trying to use old tactics in a new situation.”

Harris explains, “Capitalists have become globalized. We need to find new ways to fight. That doesn’t mean with a rife. I don’t know what it means, but we’ll need to figure it out.” He notes, “The big difficulty is that in West Virginia, our history is absolutely tied to the mines and jobs and money. I get that. What gets me is the roadblock that keeps us from reaching for our future is the experience of coal mining. It reminds me of folks in the military. It impacts the rest of their lives. Once you dig coal – I don’t back off a bit from being a coal miner (he was decades ago) – that’s the thing. The experience. If we don’t find a way to replicate that cultural bonding, we’re not going anywhere.”

Harris says having a traveling museum has afforded him hundreds of opportunities and personal encounters to share William C. Blizzard’s book and the artifacts – and stories he’s collected along the way. “The fact that I don’t have a fixed sight museum is a good thing. I teach whenever I’m out selling books. I use the artifacts to teach. People think I’m selling books. I’m not. I’m peddling history.”

“It’s just incredible. It is the history that hasn’t been told.”

Wess Harris

He continues, “I’ve had thousands go by. People ask me where I teach. I say, ‘Right here.’ My classroom is right here.” And his students are interested and engaged. “They walk up on purpose. Not for a grade or other purpose.”

Still, Harris has hopes to eventually convert the traveling museum into a permanent exhibit – in the right home, which he has not found yet. “A major university asked us to have an exhibit, but couldn’t handle the truth of it and threw us out. They just don’t know the history, the material, the period.” He hasn’t given up on the idea, though. “I must stick to the truth. I know it’s less than ideal.” There is no disputing what he is teaching is controversial. It is more than history, though, insists Harris.

“When Miners March” is instructive for our time he insists. “I’m talking about labor history, the conflict between labor and capital. What is capitalism? It’s a zero-sum game. I go at the meat of the situation. Who owns the tools? Multinational corporations own the coal. The bottom line is why aren’t we owing our own coal? What does it mean that we don’t? What does in mean to us? To some dude in New York?”

He points out that his teaching isn’t about names, dates or battles. “We start talking about the war of

extraction. I ask, ‘What can we learn?’ It’s praxis – theory and practice. When I’m farming, I integrate

theory and practice, when I’m teaching it’s all the same.”

© Michael M. Barrick, 2024, The Appalachian Chronicle

III – Note: This is the first in a series on the “When Miners March Traveling Museum” by Wess Harris.

CHARLESTON, W.Va. – Today marks the 134th anniversary of the meeting that led to the formation of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). According to e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, “On January 23, 1890, rival miners’ organizations met in Columbus, Ohio, to organize the United Mine Workers of America. Founded two days later, John B. Rae, a Scottish immigrant, became the first president. Just three months later, in Wheeling, UMWA District 17, encompassing most of West Virginia, held its first meeting, elected M. F. Moran as district president and immediately launched what became an extraordinary struggle of more than 40 years to unionize the state’s coal mines.”1

THE REST OF THE STORY

Wess Harris teaching. Photo by Nellie Blanton

Wess Harris, a sociologist, educator, author and editor, agrees that the effort to unionize West Virginia’s coalfields was “an extraordinary struggle.” However, he argues that the official accounts of the treatment of union leaders, members, and their families is sanitized by the state of West Virginia and Appalachian regional historians, sociologists, universities and museums.

He has the evidence to support his contention. In fact, as the founder and curator of the “When Miners March Traveling Museum,” he has led more than a thousand people – many college students – on what he calls “Truth Tours” to the West Virginia State Museum in Charleston. Those tours have not been received well by the powers-that-be.

“‘Written in Blood’ shines a critical light on the untold true history of the West Virginia Mine Wars.”

Mari-Lynn Evans, director and producer of “Blood on the Mountain.”

While his work has agitated those seeking to sanitize the truth, his tours are based on his decades-long

collection of hundreds of coal mining artifacts, many of them one of a kind, and is reflected in two books

Harris has edited. “When Miners March” and “Written in Blood: Courage and Corruption in the

Appalachian War of Extraction,” have caused a stir among the gatekeepers of Appalachia’s Coal Mining

history.

Indeed, Harris has converted the “When Miners March Traveling Museum” into a permanent exhibit

entitled, “Our Story.” The work of Harris and several others, it has become a living metaphor of telling the

whole truth about the tactics of coal operators. Initially scheduled for exhibit at a major university in

Southern Appalachia (more on that in a future story), the truth that rape was institutionalized in parts of

the coal industry simply proves too much to reveal. The traveling museum and books convey not only the

long history of the UMWA’s effort to secure the livelihoods and lives of their members, but shares a

startling truth that others tend to disregard, or worse, deny.

The back cover of “When Miners March,” which is about the Battle of Blair

Mountain, teaches, “Over half a century ago, William C. Blizzard wrote the definitive insider’s history of the Mine War the resulting trial for treason of his father, the fearless leader of the Red Neck Army” in the Battle of Blair

Mountain. Indeed, Howard Zinn, author of “A People’s History of the United States” said, “‘When Miners March’ is an extraordinary account of a largely ignored but important event in the history of our nation.”

Bill Blizzard, a man of courage and tenacity born in 1892, led thousands of miners in 1921 on a 50-mile march across the rugged mountains of southwestern West Virginia, culminating in the Battle of Blair Mountain. His

son, William C. Blizzard, wrote “When Miners March” in the early 1950s. Harris notes, “It is the definitive account of the West Virginia Mine Wars of the early 20th century – who shot whom, when, where and why. Too controversial to publish in the 50s, his book finally saw the light of day in

2004.”

Esau Scrip: Big Coal’s Sordid Secret

Indeed, truth is often delayed, but eventually often comes to light.

That is why “Written in Blood: Courage and Corruption in the Appalachian War of Extraction,” published in 2017 by Appalachian Community Services and PM Press is, at best, an uncomfortable read. It tells of the Esau scrip

system for women, essentially an institutionalized practice of forced sexual servitude that was part of coal company policy, at the Whipple Company Store in Oak Hill and in mines throughout the area in a radius of about 50 miles, says Harris, who says there are others across the state as well. Notably, the West Virginia online encyclopedia makes no mention of this practice.

Mari-Lynn Evans, director and producer of “Blood on the Mountain” says, “Written in Blood” shines a critical light on the untold true history of the West Virginia Mine Wars.”

Maria Gunnoe, Goldman Environmental Prize winner and recipient of the University of Michigan Raoul Wallenberg Medal, adds, “For two hundred years, the coal industry has promised us prosperity. ‘Written in Blood’ leaves little doubt that the prosperity never arrives. The promise itself is contingent on us agreeing to our own destruction. We must agree to stand idly by as they destroy our communities, water, air, health, and lives. We owe them nothing. They owe us everything.”

© Michael M. Barrick, 2024, The Appalachian Chronicle

IV – Sociologist and former underground Union miner Wess Harris asserts East Tennessee State University revoked Exhibit invitation because it revealed too much truth about how coal miners were treated by coal operators – including the Esau scrip system of institutionalized rape.

This ‘One Pounder’ fired artillery against coal miners.

It was given to Bill Blizzard by a mine operator.

Harris adds, ‘It is Field artillery used by the Our Story

Traveling Museum to blow holes in lies told by coal

companies (and others!).’ Courtesy Wess Harris.

Note: This is the fourth article about the “Our Story

Traveling Museum” by Wess Harris. Links to previous

articles are at the end of this article.

JOHNSON CITY, Tenn. – The Center of Excellence for Appalachian Studies and Services (CASS) is based here on the campus of East Tennessee State University (ETSU). According to its website, “The mission of the Center of Excellence is to promote a deeper understanding of Appalachia and to serve the region through research, education, preservation, and

community engagement. The Center is part of the Department of Appalachian Studies and consists of four components.” One is the Reece Museum, which, according to the website, ” … hosts a wide range of exhibits.”

One such exhibit was to be the “Our Story Traveling Museum” (formerly “When Miners March Traveling Museum), curated by Wess Harris, a West Virginia sociologist, former underground Union miner, and long-time critic of the way the struggles of coal miners who worked and died to form the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) is generally portrayed in “official” circles.

ETSU Reece staff suggested the exhibit

The idea for the exhibit originated at ETSU, says Harris. Reece Executive Director Rebecca Proffitt and her supervisor, Dr. Ron Roach, invited him to campus. He was teaching with his traveling museum to a class led by Appalachian Studies instructor Ted Olsen on ETSU’s campus. It was the spring of 2022. Harris shares, “I think he invited Ron and Becca in. They were blown away. They told me, ‘You’re going to be an anchor exhibit.’ They told me it would run from October 2023 until April 2024.” Indeed, Proffitt made a visit to Harris’s home in November of 2022 to get a look at the collection. Soon, plans were made to begin setting up the exhibit on Oct. 16, 2023, with the Opening set for Oct. 30 and Closing panned for April 12, 2024.

Rebecca Proffitt of ETSU visits Wess Harris in November

2022 to take a look at his Our Story Traveling Museum.

Courtesy Wess Harris.

Immediately, Harris began assembling a team of experienced, expert Appalachian scholars and Union

activists to assist with advising him on the assembling of

the Our Story Traveling Museum.

Interestingly, though emails and letters were being shared

between the parties by February, 2023, Harris apparently

operated without an Agreement from February 2023 until

June 13, 2023. (A draft Agreement dated Feb. 21, 2023

provided by Harris was signed by him, but not Proffitt;

whether or not she signed that Agreement remains unanswered). During this time, Harris and his associates

proceeded with their plans. Though pleased at the invitation, Harris remained committed to his core value of never surrendering control of the lessons he has learned from decades of collecting and curating innumerable memorabilia, artifacts, and stories of the West Virginia Union miners.

He has edited two books. His first is, “When Miners March: The Story of Coal Miners in West Virginia” by William C. Blizzard, the son of Bill Blizzard. The elder Blizzard says Harris, ” … was the chief protagonist in the drama played out around Blair Mountain” (p. i). It is the inspiration and source for Harris’s “Our Story Traveling Museum,” previously called the “When Miners March Traveling Museum.” He changed it to “Our Story Traveling Museum” because he is convinced only those involved in it – or

allies willing to listen to the people who have lived it – can and are willing to tell the full truth. That is why the ETSU invitation was a welcomed opportunity. However, Harris held firm on how “Our Story” would be told and said so as clearly as possible.

There was also an even more controversial issue. In addition to “When Miners March,” in 2017 Harris published “Written in Blood: Courage and Corruption in the Appalachian War of Extraction.” It tells of the Esau scrip system for women, essentially an institutionalized practice of forced sexual servitude that was part of coal company policy, at the Whipple Company Store in Oak Hill and in mines throughout the area in a radius of at least 50 miles, says Harris, who says there are others across the state as well. Harris made it clear to Proffitt that the Esau scrip

story must be told.

Exhibit shortened, then cancelled, both times without

warning

That’s when the collaboration turned to contentiousness, says Harris. The truth that rape was institutionalized in parts of the coal industry simply proved too much to reveal for ETSU, argues Harris. He says, that on at least two different occasions, Proffitt opposed the use of the word “rape” in the exhibit. Proffitt refused to confirm or dispute that account.

The Whipple Company Store, now privately

owned and not open to the public. Courtesy Wess

Harris.

Says Harris, “It seems that once they understood

the truth, they regretted their decsion. From the

beginning there was poor and rushed communications. We had debates over editorial control.” The staff failed to honor a vital promise – to conduct an interview of an important subject, especially to the early stages of the story, as the subject passed away before Reece staff

reached him. (Aware that the subject, Boomer Winfrey, was terminally ill, I contacted him and he graciously agreed to a phone interview just a few days before he died.).

There was a sudden and surprising change in June to the status in the exhibit by Reece staff from an anchor exhibit to a smaller, shortened exhibit. On June 7, 2023, without warning, Proffitt told Harris that the exhibit’s date and location had been changed. In an email, she wrote, “After careful consideration and much discussion with our administrators, campus partners, and Center staff, we recommend this exhibition to go forward as a 12-week installation in Gallery A. We will commit to hosting the same amount of program we would have organized for an anchor exhibition, while providing a space for you to tell the story in your own words, and exactly how you’d like it to be told.” Again, Proffitt did not explain the reason for the decision and also declined an opportunity to explain how an anchor exhibit could not

accomplish the same purpose, and arguably more effectively.

Harris observes, “I shouldn’t be surprised. They are the epitome of official Appalachian scholarship. As self-anointed caretakes of Appalachia’s history, they decided to simply censor the truth about how coal miners were treated by coal operators – including the Esau scrip system of institutionalized rape.”

Only known Esau scrip to be on public display.

Courtesy Wess Harris.

In addition, the shortening of the exhibit led to the

cancellation of appearances by documentarian Barbara

Kopple and Si Kahn, an American playwright, activist,

author and musician. Both were to visit the university

as part of the exhibit, but the date changes affected

their ability to participate as planned.

Ultimately, ETSU cancelled the exhibit, again without any prior discussion or warning. In an email dated Oct. 2, 2023, Proffitt wrote, in part, “As it stands, we were prepared to work with your provided narrative, and if you were open to receiving our edits, then this project could have moved forward – exactly in line with the schedule we agreed upon in June, and with ample time for you to have another turn to approve or re-edit until all (Proffitt’s emphasis) were comfortable with the exhibit contents.” That was how Harris learned his exhibit was cancelled – through email, the same way he had earlier learned it had been shortened and changed from an anchor exhibit.

But Proffitt wasn’t done. She continued, “Additionally, our staff and colleagues operate with integrity and professionalism, and have continued to welcome you, even though you demonstrated a lack of respect for us, both as individuals and professionals.” Neither Proffitt or Roach would reply to the basis for this characterizations of Harris.

She concluded with, “Please let me know when you will be available to come get your artifacts, preferably between October 20-27.” Ultimately, Harris picked his artifacts up on Oct. 10, 2023.

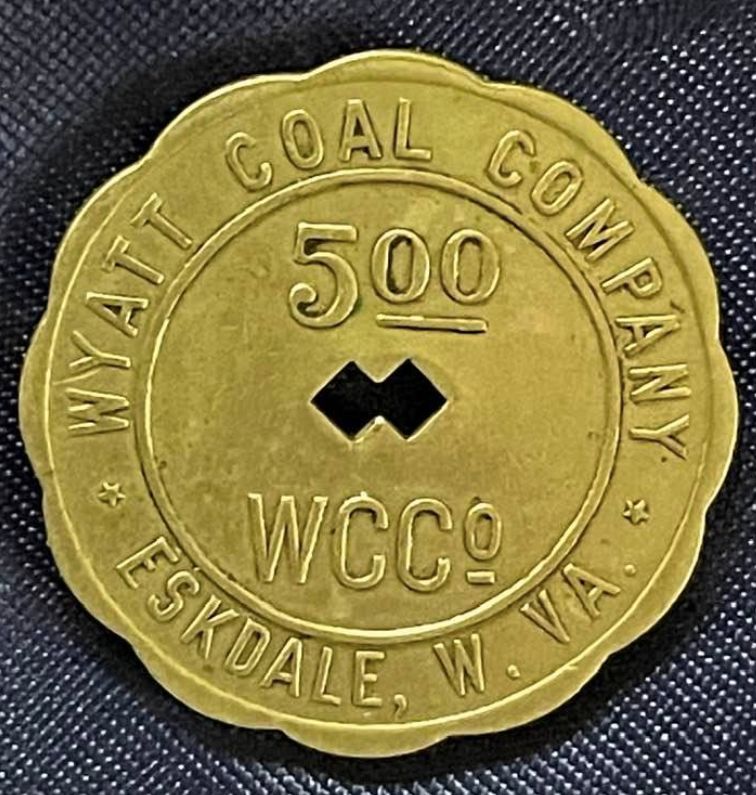

This five dollar scrip is part of the ‘Our Story’ collection that ETSU cancelled. Courtesy Wess Harris.

Moving on

ETSU seemed to be the perfect partner. In the end though, Harris says he has learned, “Appalachian history needs safeguarding from its self-anointed institutional caretakers. The very caretakers expected to be the truth-tellers – museums, universities, libraries, the media and more – will not fulfill their calling for fear of offending their corporate and large personal donors.”

He says he knows that his traveling museum is a hit. “People tell me that they know these vital stories have gone untold or

sanitized for too long. People know that and want to see the full museum in one location.” So, he carries on, wiser and as protective as ever over the story his collection and experiences teach. He is philosophical. “More cooperation is needed if we’re to overcome censorship.” He continues, “Mediocrity is not acceptable. You get it right. There is no room for error or political correctness. Just get it right!”

1911 Scrip Machine. Courtesy Wess Harris.

He also admits he made a critical mistake. He trusted people. He shares, “First, don’t do anything without signing a contract. I’m used to the West Virginia handshake, you know, like the Bible says. ‘Let your yes be yes and your no be no.’ The way I do business is not the way people do it in

academia.”

Ultimately, he has concluded, while ETSU pulled the plug, it has been right for the Our Story Traveling Museum. “If I’m going to work with you, I must be willing to work a shift with you in an underground mine and walk a contested picket line. ETSU staff don’t meet that standard. They do not understand their history.”

Wess Harris with a Connie West portrait of Willard Uphaus from his ‘Our Story’ collection. It is just one of dozens of portraits that would have been displayed. Photo by Nellie Blanton.

Efforts to speak with ETSU staff

I contacted ETSU numerous times to interview Proffitt or Roach for this article. They refused to answer the questions or agree to requests for an interview.

Furthermore, on April 5, 2024, I sent Proffitt about eight questions with background for the reasoning of the story, copying Dr. Roach. On April 8, I called Proffitt to verify she had received my email. She denied having received it, though it never bounced back. She did offer that Roach had received it and “was passing it around the university to different people to see if I should answer the questions.” I followed up immediately with an email to Roach and Proffitt. Neither email bounced back. I sent a second one, suggesting that lacking evidence of it bouncing back, it was safe to expect that Proffitt had, indeed, received the email. On April 11, I called Roach and left a message on his answering device. I have never heard back from either individual or any other ETSU representative.

Conclusion

It would seem that the Reece team did not take to heart a letter from Appalachian Scholar and Activist

Theresa L. Burris, Ph.D. In writing a contextual essay in support of the Our Story Traveling Museum, she

wrote, “On the back of an envelope mailed to me on February 19, 2008, Wess Harris hand wrote, ‘Danger!

Contains Ideas!’ This witty, apt warning epitomizes Wess’s character and approach to life.

Previous Articles

– Wess Harris Reveals His Unlikely Path as Curator of ‘An Incredible History that Hasn’t Been Told’

(02/27/24)

– The Rest of the Story: The ‘When Miners March Traveling Museum’ by Sociologist Wess Harris

(01/23/24)

– The First Coal Wars and the Convict Lease System – Preserving the Teaching of ‘Boomer’ Winfrey

(11/23/23)Previous Articles

Disclaimer

I was on the ETSU campus twice with Mr. Harris. The first time was on June 13, 2023 at the request of a mutual acquaintance. My input regarding the Exhibit was sought. I met Ms. Proffitt and others then, but only for a very brief time. The second time was on Oct. 10, 2023 when, again, I met Harris on the campus at his request as he reclaimed his collection. – MMB

© Michael M. Barrick, 2024, The Appalachian Chronicle