Convict Labor/Tennessee Battles

Convict Mine

In 1876 the first convicts were brought into Coal Creek to replace Welsh and local Appalachian miners following a labor dispute at the Knoxville Iron Company mine. Since mining jobs with other companies were plentiful, little was done and the convict mine was allowed to operate without interference for the next 15 years.

Early Coal Creek photos are on display at the Coal Creek Miners Museum. Narratives courtesy of “Boomer” Winfrey.

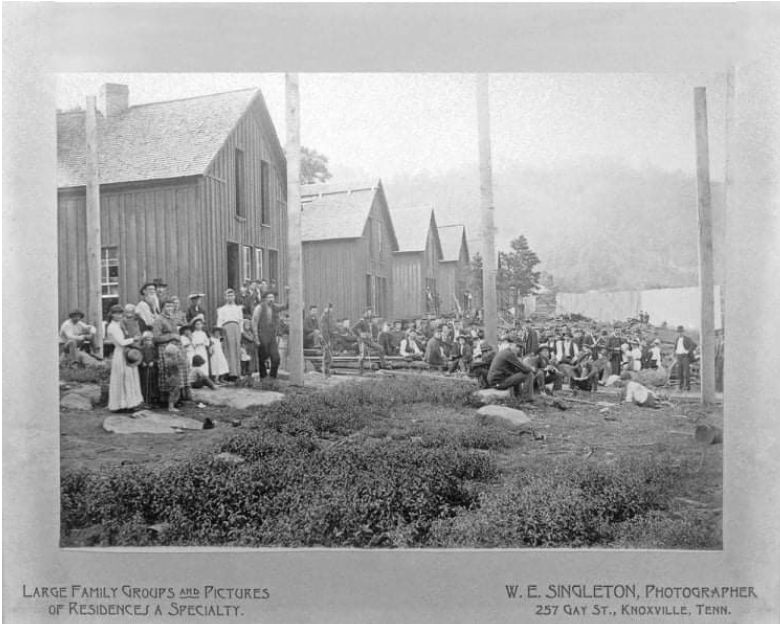

Evicted Families

In the summer of 1891, miners at the Tennessee Coal Mining Company in Briceville accused the company weighman of cheating them on their wages. The company responded to threats of a strike by bringing in convicts. The prisoners first task was to evict the miners’ families from their company-owned homes and use the lumber to build their own prison stockade. The photo above shows the evicted families gathered outside their homes as the stockade (light structure in right background) begins to take shape.

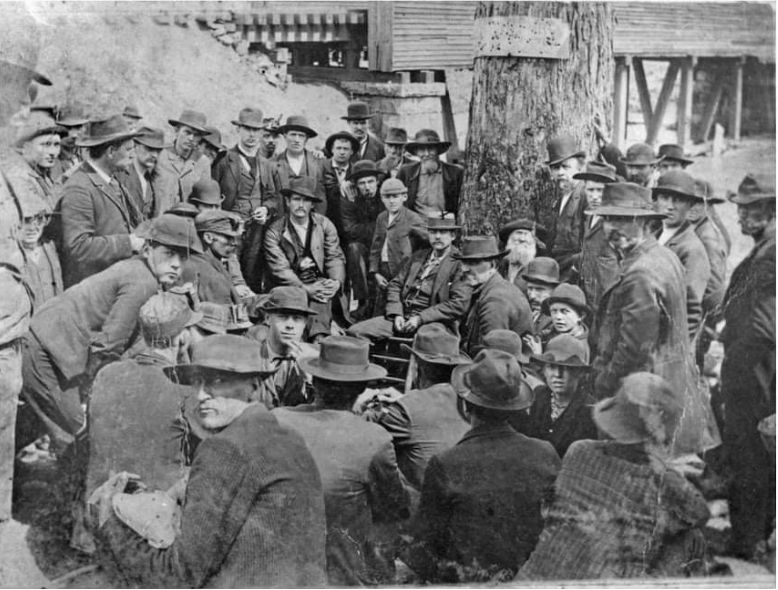

Miners Revolt

This time Coal Creek miners fought back. On July 15, 1891, a force of over 500 armed miners and citizens marched on the Briceville stockade, forced the guards to surrender and loaded both guards and convicts on a train for Knoxville. In this photo, miners are meeting to plan their response after learning that Governor John P. Buchanan is on his way to Coal Creek with a company of State Militia to return the convicts.

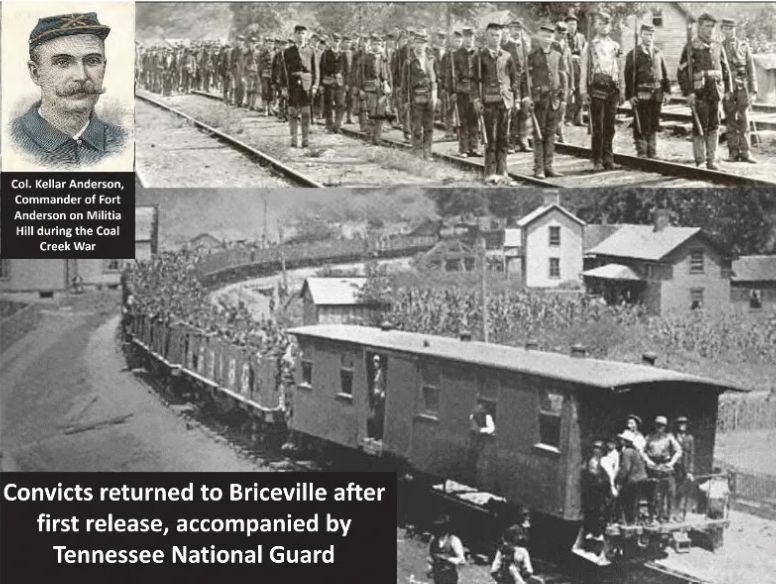

Twice again in 1891, miners, reinforced from as far away in Kentucky, marched on the convict stockades. Feeling betrayed by the legislature, miners finally burned the stockades at Briceville and Oliver Springs and set the convicts free. The State of Tennessee responded by establishing a permanent garrison of militia in a fort overlooking the Knox Iron stockade, under the command of Col. Keller Anderson.

1892 — The Final Act. After an uneasy winter and spring, coal miners again rebelled, placing the garrison at Fort Anderson under siege. Over a thousand troops were rushed to Coal Creek to break the rebellion once and for all. The men of Coal Creek were forced to lay down arms and surrender or watch their town and homes destroyed by artillery fire. Hundreds were arrested and Coal Creek was placed under martial law and military occupation for most of the following year.

The cost of keeping an army in the field to enforce the system proved greater than the profits from leasing convicts. Tennessee constructed Brushy Mountain State Prison and put convicts to work mining coal for state buildings instead of competing with free labor. The rest of the South slowly followed Tennessee’s lead until the practice was brought to an end once and for all.

Pictured above is the Tennessee National Guard at Fort Anderson on Militia Hill during the Coal Creek War.

And Coal Creek, Tennessee

Blotted, too.

Pleasure-seeking tourists at

“Lake City” don’t know

the bitter — and glorious–

story of Coal Creek.

Change the name

Blot the memory….!

Hope and hurt, blood and terror

lie heavy in Coal Creek memory.

Mountain men there lit the spark

destined to destroy

the convict labor system.

In 1891 they were called “Communists!”

Don West

Lake City is no more. The name has been changed (again)…..now to Rocky Top in yet another futile attempt to attract tourists.

Fort Anderson Trench

This week the OUR STORY TRAVELING MUSEUM offers up another gem of Union history in Anderson County, TN.

The defensive trench remains around Fort Anderson. The cannon fired upon miners from behind wooden walls long lost to the ravages of time. Miners soon discovered that the fort held the high ground above town but not the highest ground. A bit of a hike and miners could be on higher ground and the trenches were not safe from snipers.

Official history tells us that the militia fired canisters of mud upon the town as a warning that it could be destroyed at any time. Sanitized history! The canisters were filled with brown stuff but not mud. It was not safe to venture into the trenches to recycle last night’s beans so after extracting needed nutrients the remains were shot into town as a donation of fertilizer for gardens! Could this be in some way the origin of the saying “shoot the shit”.

This is a marker at a cemetery for Welsh miners. They also buried black miners killed in mine explosions. The Black miners were not allowed burial in all-White cemeteries.

Power and Powerlessness

This week the OUR STORY TRAVELING MUSEUM offers John Gaventa’s classic study of power and lack thereof in Coal Country. Recent events (think Alabama) coupled with my ongoing work in East Tennessee make this a compelling choice. To my Union brothers and sisters everywhere if you have not read this— no, studied this, do so. If you have (for me roughly 30 years ago), read it again!

And again John is among the very best sociologists of our time. His analysis cuts like a knife. His truths have not been diluted with time. We can hardly expect to win if we fail to reflect up why we lose.

Meanwhile, thanks to John Gaventa and all who expect excellence, as the saying goes, if ay can’t stand the heat, git out of the kitchen. Or learn to cook….